An Interview With Fotis Georgiadis

I don’t believe in alliterative lists or “mottos.” But I do believe words express a way of thinking.

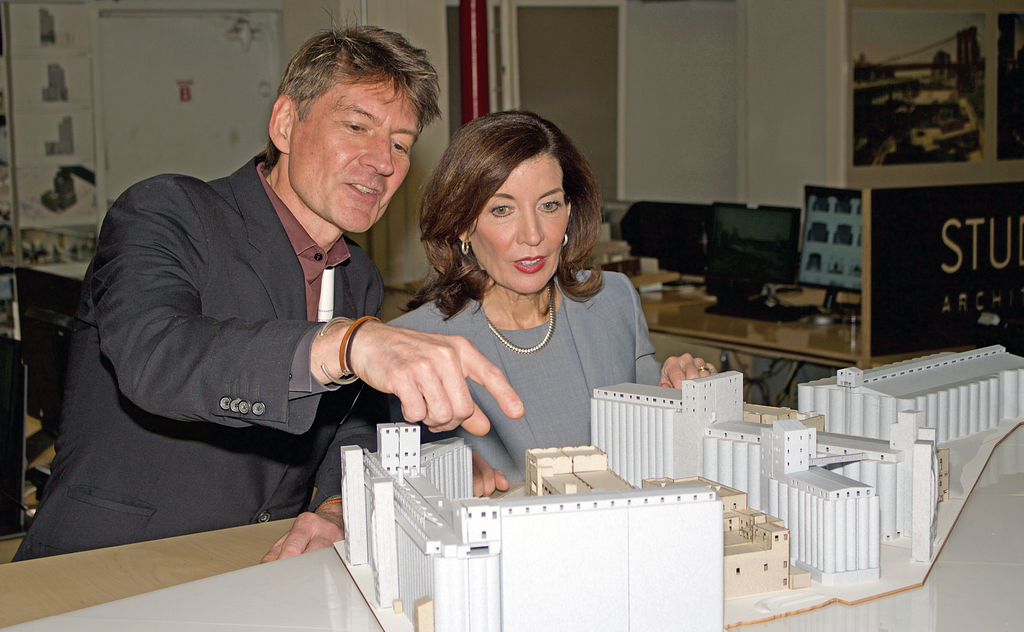

As a part of our series about business leaders who are shaking things up in their industry, I had the pleasure of interviewing Jay Valgora.

Jay Valgora, FAIA, AICP, LEED AP, WEDG, is founder and principal of STUDIO V, a cutting-edge design practice dedicated to the reinvention of the 21st century city. He leads a talented group of designers creating unique buildings, public spaces, and transformative urban design, reconnecting innovative architecture with urbanism. His designs focus on the edges and gaps of cities — industrial and contaminated sites, divisive infrastructure, former urban renewal, historic and industrial artifacts, and waterfront’s potential to address climate change and reconnect communities.

Jay was born in Buffalo where the abandoned grain elevators and the industrial waterfront inspired him to become an architect. He is a graduate of Harvard and Cornell and a Fulbright Fellow to the United Kingdom. Jay advised on NYC’s Comprehensive Waterfront Plan, was appointed by the mayor to NYC’s Waterfront Management Advisory Board, headed the New York AIA Waterfront Initiative, and sits on the Advisory Board of NYC’s Urban Land Institute. Jay has lived in many cities — but he has never owned a car.

Thank you so much for doing this with us! Before we dig in, our readers would like to get to know you a bit more. Can you tell us a bit about your “backstory”? What led you to this particular career path?

My story begins with climbing fences. I was born in the shadows of the steel mills where my father worked near Buffalo, New York.

When I was young, I would go places I wasn’t supposed to, jumping fences, and climbing barriers to explore cut off waterfronts and abandoned buildings. I was fascinated by the industrial ruins, the towering, abandoned grain elevators, and the seemingly endless industrial buildings where my father worked. I felt like you could see the curvature of the earth in them.

Buffalo is one of the greatest designed cities in America, with magnificent architecture, vast networks of world class parks, and a stunning sense of place along the great inland ocean of the Great Lakes. It’s also evolved into one of the greatest ruined cities in America with industrial decay, abandonment, red-lining, and the destruction wrought through so called urban renewal. This inspired me to become an architect to create buildings that engage the city, breathe new life into abandoned industrial structures, and public spaces that reconnect communities.

Now my work is all about breaking down fences.

Can you tell our readers what it is about the work you’re doing that’s disruptive?

We solve problems by making them more complex.

Most architects attempt to “solve the problem.” Given a complex problem — they immediately start to isolate complex issues, simplify them, attempting to reach one solution. After finding that solution, the architect works feverishly to convince everyone of the “right” solution and “protect” a design through the gauntlet of client’s needs, budget, and construction.

STUDIO V takes the opposite approach. To solve a problem, add layers of complexity that speak to the underlying forces that created the problem to address that but offer greater richness and meaning.

For example, our design for Empire Stores. This was a competition to transform seven magnificent 19th century coffee warehouses, abandoned for a half century on the most prominent site on the Brooklyn waterfront. The problem: rehabilitate abandoned historic buildings and convert them to commercial uses.

Instead of solving that problem — we created a new one.

The Empire warehouses were called “stores” (as in “ship’s stores”) and together, they comprised “Fortress Brooklyn,” a wall of continuous historic warehouses that originally separated upland communities from their dangerous working waterfront. We immediately made the very unusual suggestion: restore the historic buildings by cutting a hole through the middle of them.

This was a pretty non-intuitive idea, to take a ruin and repair it by cutting a hole through it. But from this way of making a problem more complex, not just “solving” it, we worked with many people to find overlapping benefits: This opening would form a sequence of public spaces to reconnect the community. It would activate the building and promote more complex programs and uses (restaurants, offices, tech showcases, a museum, a public park). It would provide authentic material to repair missing parts of the building (historic brick, timber). It would admit light and life into the heart of structures originally designed to keep coffee beans cold and dark. It would create a public realm to reconnect the community.

The bottom line: the public spaces drove traffic and created a civic realm, connecting the park and community. The commercial spaces became the most successful in Brooklyn. Funds from those spaces support the public programming of the park. Private investment rebuilt buildings that were abandoned for a half century. And Empire Stores won every architecture and civic award the city had to offer.

I like to combine things that don’t belong together- old and new, edge and center. This applies not just to architecture, but how we engage people and process: we work equally with non-profits and developers and government officials and activists. Our projects combine experimental work with huge developments. We wade into situations with intractable problems and create a culture of using design to offer new answers.

Can you share a story about the funniest mistake you made when you were first starting? Can you tell us what lesson you learned from that?

When I started STUDIO V, designing our own space started off as a disaster.

I founded STUDIO V sixteen years ago and asked a friend if I could rent a few desks in his office. He agreed — but then lost his lease at the last minute! Needing a new office, he found a larger space, but asked me to take half with a ten-year lease. I was terrified but there was no time, and all I wanted was just a few desks!

I took a risk and said “yes” only now we had to renovate a raw space with little time. After a very modest renovation, I didn’t have money to buy furniture and my friend offered to give me his leftovers, odds and ends of a few desks and chairs. I was lucky to hire an amazing first employee, John. He’s still a legend at STUDIO V. When John came in, the office was only partially constructed, and pieces of desks and chairs were lying on the floor. John took one look, and calmly asked for a screwdriver. He offered to put it together so he could sit down and start work.

And I always remember for years after, John said it wouldn’t have been a real startup when he showed up on day one, if he didn’t have to assemble his own desk.

We all need a little help along the journey. Who have been some of your mentors? Can you share a story about how they made an impact?

My greatest mentors come from family and a few remarkable teachers.

My father is a great influence. As a child, he took me to an original, primordial island, the size of Manhattan, covered with woods and lakes in their original unchanged state (we don’t say where, but far to the north). I return throughout my life to this vast and largely still unexplored island, now with my own children. The landscape and experiences of this special place provide a sort of touchstone of utopia that influences my work, and a counterpoint to the island metropolis of New York in which I live.

A few teachers had an outsized influence. At Harvard, I studied under Alvaro Siza, the brilliant, world-renowned architect. Siza taught me the importance of reinterpreting modernism and fusing them with a richness of spatial experience and profound humanism. At Cornell, I knew Colin Rowe who influenced generations of architects. I would sit on juries at Cornell’s first program in Rome, then walk around the ancient city while Colin made extraordinary and wild leaps of insight into the relationship of classical ideas and the modern world.

In today’s parlance, being disruptive is usually a positive adjective. But is disrupting always good? When do we say the converse, that a system or structure has ‘withstood the test of time’? Can you articulate to our readers when disrupting an industry is positive, and when disrupting an industry is ‘not so positive’? Can you share some examples of what you mean?

Cities are our greatest work of art, and my work is all about the reinvention of cities.

But one of the most disruptive urban transformations in the history of cities was a drastic form of city reinvention called “Urban Renewal.” Urban renewal was one of the most destructive transformations of our urban environment. It destroyed entire neighborhoods, tore through them with infrastructure, and used devastating tools like red-lining and “blighting” to erase large areas of collective history.

The two historical events that most influence my work are industrialization and urban renewal. Much of my work focuses on the edges and gaps these forces left within our cities and the opportunity these sites offer today. My designs attempt to restore and reinvent sites that bear the scars of industrialization and urban renewal and invest them again with the richness of meaningful forms, public spaces, and history, to weave them back into the community.

Can you share five of the best words of advice you’ve gotten along your journey? Please give a story or example for each.

I don’t believe in alliterative lists or “mottos.” But I do believe words express a way of thinking.

So here are five simple words I use every day:

“see” looking and seeing are not the same things; we look in order to “see”.

“draw” the first step to seeing — drawing is choosing, representing, seeking.

“create” the act of making starts with seeing and drawing.

“explore” making requires questioning and evaluating every choice.

“recreate” both senses: starting again and refreshing: beginning the process all over.

In a world of computers and complexity, I still draw by hand every day, working with a talented group of people and using these five simple words to infuse the process of everything we design.

We are sure you aren’t done. How are you going to shake things up next?

We’ve spent years building up our practice and skills to reinvent communities and cities. Now we’re ready to reinvent ourselves.

We just purchased a small building in Manhattan a few blocks from our current space, in which we will move our Studio. Our goal is to re-make and redesign ourselves. We have to decide what will define the next stage for STUDIO V and are looking at some exciting ideas: how will we engage the street with a storefront studio? How can we create a more creative workplace? Can we create a garden for our designers?

Do you have a book, podcast, or talk that’s had a deep impact on your thinking? Can you share a story with us? Can you explain why it was so resonant with you?

I listen to podcasts, go to lectures, stay up into the night talking ideas with friends and strangers. I love to read, but for “deep impact,” you’ve got to go for the stuff that transcends.

So I’ll toss out the poet Virgil, and his great work, The Georgics.

It’s the strangest thing: sort of a classical Farmer’s Almanac. It’s ostensibly about “agricultural matters” and a description of how to raise crops and livestock. But as an architect, it’s really a remarkable poem that defines a way of thinking about how we make our world. It’s a dissertation on man’s place in the world, how we make and cultivate our vision of that world, and a wild utopian and dystopian ride into our greatest aspirations, fears, and dreams.

Can you please give us your favorite “Life Lesson Quote”? Can you share how that was relevant to you in your life?

As part of the disruptor vibe, I’m going to swerve from the life lesson deal, and go for something that speaks more to me. I’m talking poetry, and I see Walt Whitman as one of the first to express a truly American “voice.”

Here’s a tiny piece of the poem “Under Brooklyn Ferry,” better known as “the Sun-Down poem.” Whitman does this crazy thing; he reaches out to us from the past, from his time into our time, and literally speaks to us. And he speaks incredibly optimistically, describing the growing and exuberance of the city around him, knowing we will live and experience it as he did, and offering us a vision of the individual and the city:

Just as you feel when you look on the river and

sky, so I felt,

Just as any of you is one of a living crowd, I was

one of a crowd,

Just as you are refreshed by the gladness

of the river, and the bright flow, I was

refreshed

The poem combines so many things that I think about, all the time. The river and the city’s edge. How we are drawn to the edges of a city, temporarily leaving it and yet within it. Whitman speaks about what makes our collective experience in the city. And in an incredibly optimistic way, he fearlessly speaks to you and me, knowing we will hear him, and understand him, giving us hope and a greater sense that we are part of a collective enterprise that encompasses all of us.

It’s helpful to remember today — this is a guy who lived during a devastating time of dramatic upheaval and civil war, but he was one of our greatest unrepentant optimists.

You are a person of great influence. If you could inspire a movement that would bring the most amount of good to the most amount of people, what would that be? You never know what your idea can trigger. 🙂

I would offer a new riff on the building code. It would require a garden or green space, for every residence, for every person. Not a luxury — but a necessity for living.

How can our readers follow you online?

Check out our work on instagram

Even better: go see our buildings and spaces IRL

Visit Empire Stores, climb up through the public courtyard to the rooftop park, and write us a note, letting us know what you think.

This was very inspiring. Thank you so much for joining us!

Meet The Disruptors: Jay Valgora Of STUDIO V On The Five Things You Need To Shake Up Your Industry was originally published in Authority Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.